The Cybernetic Fate of Organisations

In our previous post, we explored how Panarchy and adaptive cycles help us understand the dynamics of change in complex systems. We saw how systems evolve through growth, conservation, release, and reorganisation. But how can leaders influence these cycles and guide their organisations toward a better future?

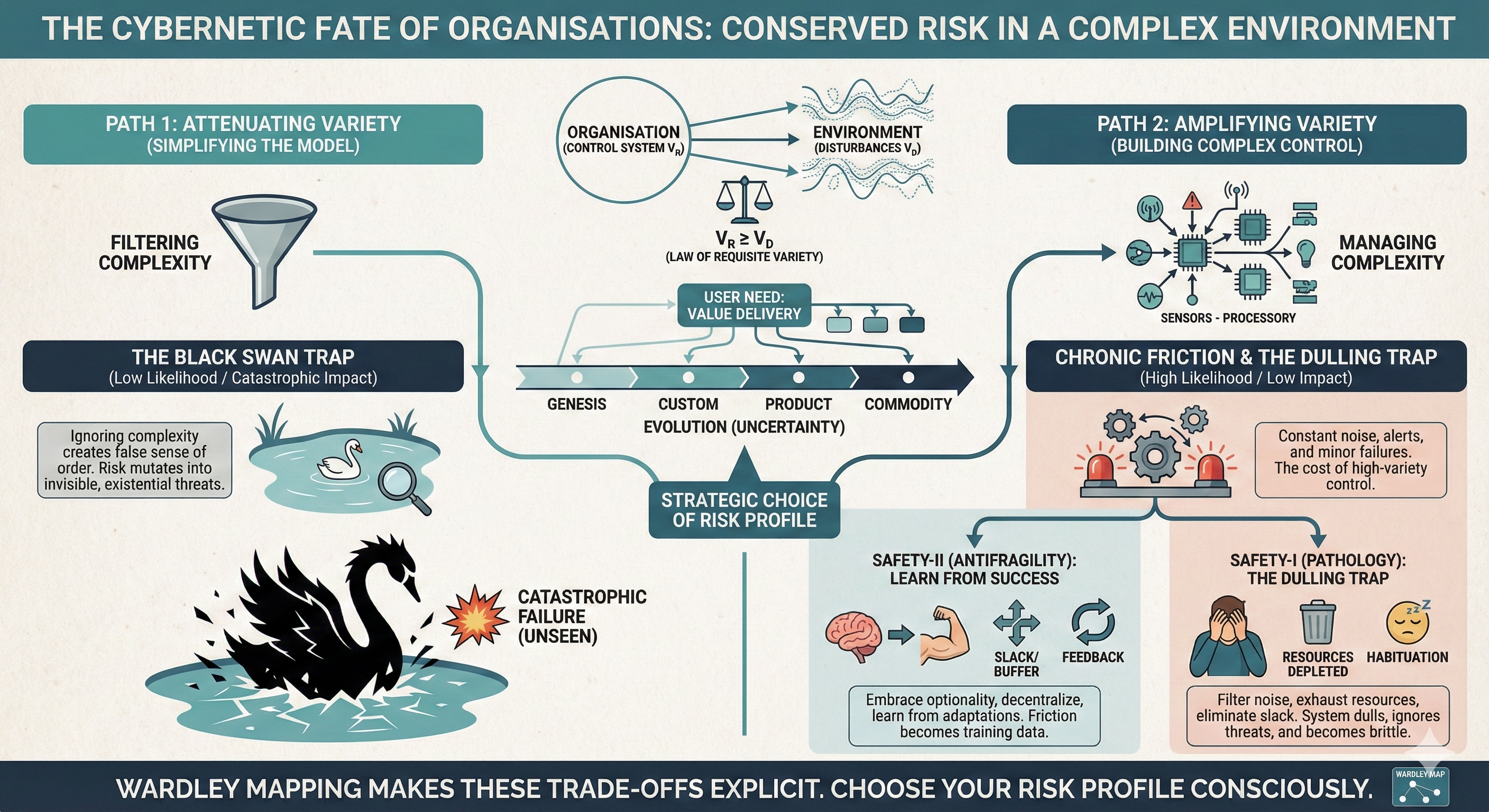

Many leaders see Wardley Mapping as a tool for visualising competition, not as a lens for understanding risk. This post bridges that gap. It shows how the cybernetic Law of Requisite Variety (LRV)—the idea that a control system must be as complex as the environment it’s trying to manage—and Wardley Mapping can reveal the hidden trade-offs organisations make when dealing with uncertainty.

Risk isn't eliminated; it's conserved and reshaped by the strategic choices an organisation makes about complexity.

The LRV states that the variety (V) of your control system must be at least equal to the variety of disturbances from the environment:

The LRV states that the variety (V) of your control system must be at least equal to the variety of disturbances from the environment: V_R ≥ V_D. 'Variety' is just a way of counting the number of different states a system can be in. For an organisation in a volatile market, the real decision isn't about reducing risk, but about transforming the risk it can't get rid of. This transformation depends on a choice of risk profile, which boils down to a trade-off between the likelihood (L) and the impact (I) of failure. This leads to two cybernetic traps: the Black Swan Trap, where hiding from complexity leads to rare, catastrophic shocks, and the Dulling Trap, a result of amplifying complexity in a pathological way.

Map the Risk Surface Before You Shape It

Wardley Mapping brings discipline to this conversation. By visualising the value chain—from user need to the components that satisfy it—and placing each component on the evolution axis, leaders can make the implicit trade-offs of the LRV explicit. A map shows whether the organisation is relying on undeveloped, high-uncertainty components (in Genesis and Custom Build stages) or over-investing in industrialised, commodity capabilities. Climatic patterns like "Efficiency does not mean a reduced spend" and "Competitors' actions will change the game" warn us that ignoring how components evolve invites new problems. Doctrines like "Focus on user needs" and "Use a common language" push us to sense and respond with the right techniques for each evolutionary stage. These insights from mapping prepare us to see how complexity is being either reduced or amplified.

A practical technique is to annotate the map with the teams or systems ('regulators') responsible for each stage. This quickly highlights where regulators are overloaded with complexity that is far from the user need. It also opens up collaborative conversations with risk and assurance teams, who rarely see their work plotted on such a clear landscape.

Dilemma I: The Black Swan Trap and the L/I Trade-Off

Standard risk management, as formalised by frameworks like ISO 31000, evaluates risk by multiplying likelihood (L) by impact (I) and tries to mitigate any score that seems too high. When organisations face complexity (V_D) that far exceeds their capacity to manage it (V_R), the most common response is to reduce that complexity, or 'attenuate variety'.

Variety attenuation is the deliberate act of simplifying the model of the environment—filtering out disturbances that seem irrelevant, trivial, or statistically unlikely. In Wardley terms, this often means redrawing the map to focus only on the industrialised parts of the value chain, assuming that the volatile Genesis and Custom-built elements can be ignored or outsourced. In practical terms, this is an organisation's faith in abstractions. We choose to believe that a vast, high-variety reality can be successfully managed with a simpler, lower-variety representation, thus satisfying the equation V_R ≥ V_D (filtered).

The Trap of Low Likelihood / Catastrophic Impact

This strategy, while offering immediate operational efficiency, fundamentally reallocates risk:

Controllable risk, when attenuated, mutates into low likelihood × catastrophic impact exposure.

By choosing to exclude complex disturbances, the organisation turns predictable, high-likelihood operational issues into a low-likelihood, existential threat. The control system lacks the variety to even sense the new, ignored disturbance, ensuring complete paralysis when the abstraction inevitably fails. On a Wardley Map, this is the moment an unobserved component jumps from Genesis to Product in a competitor’s value chain, blindsiding the complacent incumbent. This is the Black Swan Trap: the organisation has traded its ability to anticipate for a false sense of short-term order, leaving it critically exposed to the rare, high-magnitude event that exploits the gaps in its simplified worldview. The low risk score is a hollow victory, achieved only by blinding the system to its own most lethal vulnerabilities.

Example: A financial services provider maps its fraud-detection capability and outsources experiments with new data sources because they are in the Genesis stage. For three planning cycles, it reports lower operational risk. When an unexpected type of fraud emerges, the outsourced partner can't pivot fast enough, and the in-house teams no longer have the situational awareness to respond. The apparent efficiency of reducing complexity created a Black Swan exposure that only became visible when mapped over time.

Dilemma II: Chronic Friction and the Dulling Trap

If an organisation rejects the Black Swan Trap, it must amplify its variety, building a control system (V_R) complex enough to match the environment (V_D). This leads to a second dilemma: the rise of chronic operational friction—a steady state of high-likelihood, low-impact events.

This endemic friction—frequent alerts, process bottlenecks, minor failures, and high overhead—is the informational entropy that a complex control system needs to maintain order. It is the cost of constantly processing and responding to a high-variety environment. Wardley’s doctrine of "Use a common language" reminds us that situational awareness decays when teams can't interpret signals consistently. The question then becomes: is this friction making us stronger, like a gym, or is it a slow poison?

Antifragility: The Safety-II Mandate

Chronic, mild risk can be a pathway to antifragility—the ability to gain strength from disorder—but only if the system is designed with a Safety-II philosophy.

Safety-II is a cybernetic perspective that shifts the focus from "what caused the failure?" to "how did the system succeed most of the time?" In a high-variety environment, the frequent minor events are not seen as failures to be eliminated, but as successful local adaptations where the system absorbed a shock without catastrophic impact.

An antifragile organisation:

- Maps edge authority intentionally: It decentralises control in line with the map, pushing control and resources to the edges of the value chain where components are still evolving and uncertainty is highest. This allows local agents to react quickly to friction.

- Embraces optionality: It maintains enough slack (time, budget, redundancy) to allow local failures to occur safely. This buffer turns a shock into a low-cost, high-value data point and funds the Wardley doctrine of "Be prepared to change."

- Learns from success: It installs rapid feedback loops that force the organisation to analyse why the system didn't collapse during a near-miss, constantly updating its

V_Rwith the variety it absorbed during the crisis. Each loop is a map update that records component movement and informs the next strategic play.

In this mode, operational friction is a productive micro-stress that helps the system’s adaptive muscle grow, continuously satisfying the LRV at an evolving level of complexity.

Organisational Dulling: The Safety-I Pathology

The same high-likelihood, low-impact friction becomes pathological when the organisation operates under the rigid control paradigm of Safety-I.

Safety-I is the traditional approach of defining safety as the absence of failure, demanding a "Zero Harm" or "Zero Defects" environment. When faced with constant, low-impact friction, a Safety-I organisation responds destructively:

- Pathological filtering (habituation): Since the organisation can't eliminate the chronic alarms, staff begin to filter them out as noise. This 'organisational habituation' consumes the system’s attention—the finite resource of focus required to differentiate a threat. When a new, serious disturbance occurs, the signal is ignored because the system is numbed by constant, repetitive friction. In mapping terms, situational awareness collapses, and doctrines like "Focus on user needs" or "Challenge assumptions" wither.

- Resource depletion: The centralised, bureaucratic effort to log, investigate, and mitigate every minor, high-likelihood failure consumes the resources (time, specialised personnel, capital) needed to develop defences against rare, acute threats. The system becomes exhausted by its own operational overhead, and the map becomes a fossil of outdated assumptions.

- Elimination of slack: The drive for Safety-I efficiency often leads to the eradication of redundancy and buffer capacity. This makes the system brittle and unable to absorb any unexpected shock, invalidating the original strategy of amplifying variety. Climatic forces like "Higher order systems create new sources of value" then strike without resistance.

Conclusion

The LRV forces an organisation to choose its risk profile. To an expert, the total risk might look the same on a standard ISO 31000 risk matrix—whether it's high impact/low likelihood or low impact/high likelihood—but the strategic outcome is radically different.

The Black Swan Trap is an existential threat hidden behind a thin layer of abstraction. The Dulling Trap is a more insidious, chronic threat, where the organisation uses its complex control systems to generate constant, unproductive noise that fatigues its most crucial resource: the capacity for a new, adaptive response. The ultimate cybernetic mandate is to embrace complexity through the Safety-II paradigm. This ensures that chronic friction is actively metabolised into superior adaptive variety, rather than being allowed to degenerate into pathological noise that dulls the system’s senses and invites catastrophic failure. Wardley Maps provide the situational awareness to see which components are at risk, which doctrines need reinforcement, and which strategic plays will conserve risk in a form the organisation can transform into a strategic advantage.

Key Takeaways

- Map regulators as well as components. You can't manage complexity you can't see; make the responsible teams visible on every map.

- Choose your trap consciously. Hiding from complexity invites a Black Swan, while unmanaged amplification of it invites organisational dulling.

- Build antifragile routines. Treat chronic friction as training data by resourcing decision-makers on the edge, keeping slack in the system, and learning from successful adaptations.

- Close the loop with doctrine and plays. Reinforce doctrines like "Focus on user needs" and "Use a common language" with practical experiments, so the map evolves with reality.

References

- Ashby, W. R. (1956). An introduction to cybernetics. Chapman & Hall. http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/books/IntroCyb.pdf

- Hollnagel, E. (2014). Safety-I and Safety-II: The past and future of safety management. Ashgate. https://www.routledge.com/Safety-I-and-Safety-II-The-Past-and-Future-of-Safety-Management/Hollnagel/p/book/9781472423085

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018). ISO 31000:2018 Risk management—Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html